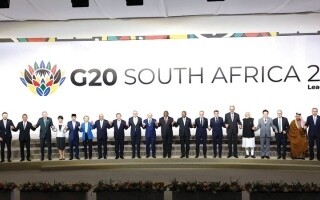

On December 1, the United States assumed the rotating presidency of the Group of Twenty (G20), succeeding Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa—nations of the Global South. Over the past four years, the group's agenda and membership have evolved significantly, completing the first full rotational cycle. Since the G20 summits transformed from modest annual meetings of finance ministers into leader-level forums in response to the global financial crisis that erupted in the fall of 2008, every member country has held the presidency at least once. For the first time since 2009, the G20 presidency has returned to the United States. The G20 comprises Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, the European Union, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In a joint analysis published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Senior Fellow Gustavo Romero and Director of the Global Order and Institutions Program, Stewart Patrick, stated that the transition of the G20 presidency to the U.S. will be "more than a mere procedural formality; it represents a fundamental shift from a broader, more inclusive, and development-focused vision for the group to a narrower, more nationally focused one." Furthermore, the Trump administration has signaled its intention to steer the group back toward a more traditional approach, which will likely result in a sharp rollback of much of the progress made in the last four years. This shift raises fundamental questions about the G20's purpose, legitimacy, and effectiveness at a time when multilateralism itself is under increasing pressure. This transition presents a prime opportunity to assess the G20's trajectory and its importance in global economic governance. The past four years under the leadership of Global South nations marked a distinctive phase in the G20's evolution. For the first time, two emerging economies consecutively held the presidency, a continuity of great significance. These presidencies were also characterized by remarkable consensus, providing a degree of continuity to the group's work, especially as the summits in Bali, New Delhi, Rio de Janeiro, and Johannesburg shared many common themes. The first of these themes was the persistent pursuit of greater inclusivity and representation. India's 2023 presidency was a pivotal moment, securing permanent African Union membership and significantly expanding the group's representation of global GDP from 65% to 80%. By the time of South Africa's 2025 presidency, the organization had 22 working groups, three task forces, and 13 teams focused on issues like labor and science. The second major theme was the debt crisis and reform of the international financial system. During their presidencies, Indonesia and India emphasized the need to strengthen multilateral development banks and accelerate progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals. Brazil prioritized reforming international financial institutions, while South Africa elevated the issue of sovereign debt restructuring and development financing, stressing the inadequacy of current mechanisms and the dangers of opaque, protracted debt settlement processes for the financial and economic stability of Global South countries. Additionally, the four southern presidencies highlighted climate change as a developmental challenge rather than an isolated environmental issue. Finally, these presidencies succeeded in embedding issues of inequality, social protection, and hunger at the core of the G20's deliberations. With the Trump administration now at the helm, it has already indicated that the U.S. presidency will focus on economic growth, deregulation, energy security, and technology, which will inevitably curtail the G20's work in areas like climate change, inequality, and development. While scaling back the G20's broad agenda is not necessarily an error—given the group's origins as a limited forum and that expansion may have harmed its cohesion—the extent and manner of this reduction are of paramount importance. At the same time, a repeat of the period of U.S. disengagement from the group, as seen during Trump's first term, would be the worst-case scenario for the G20 in 2026. However, this scenario seems unlikely, as the U.S. now holds the presidency. Instead of adhering to the preferences of other governments, the American administration will have the freedom to impose its vision and set the direction. The most likely outcome is that 2026 will be a turbulent year for the G20, marked by transactional diplomacy, repeated threats of tariffs, and disregard for institutional continuity or diplomatic norms.